Former St. Pete Mayor Reveals Playbook for Blocking Black Housing Development; Antique Documents Shed Light on Structural Racism

– By Gypsy C. Gallardo

In 1948, St. Petersburg Vice Mayor Samuel Johnson (who later served as mayor, 1951 to 1957), openly confessed to the collusion of city officials and staff in a years-long effort to prevent Black residents and developers from buying and building homes in white areas of the city.

The incident was remarkable for several reasons, including the fact that his words were not accidental or off-the-cuff. He did not slip and spill the beans.

When Johnson confessed his crimes, he was reading from a carefully prepared statement, pre-approved by his fellow Councilmen, for public airing at a City Council meeting, and apparently supplied for reprint to the St. Petersburg Times.

I’ve provided Johnson’s statement below, but before that, here is a quick recap of some of the events that led Johnson – in “desperation” – to speak so openly about the tactics used to prevent “an encroachment of Negroes” into white areas of the city.

Events Leading to Johnson’s Confession

It was February 1948 and city leaders were grappling with what to do about the increasing push by African Americans to buy and build homes in white areas, in part because of the increasingly dangerous and congested housing conditions in the “Negro section” of St. Petersburg.

Tension around the issue had been building for years due to a combination of factors. For one, Black neighborhoods were bursting at the seams. St. Pete’s African American population had more than doubled since City Council officially set boundaries for where they were permitted to live.

Despite reports of overcrowded and slum-like conditions in Black neighborhoods by the federal Works Progress Administration (WPA) in 1940, the city planning department in 1943, and the National Urban League in 1945, city leaders had so far done nothing to alleviate the problem.

Meanwhile, a spirit of Black activism was quickening. African Americans and white moderates had began to challenge the power structure with greater frequency and success.

In the three years before Johnson’s proclamation, white supremacists suffered back-to-back public defeats, including the 1945 firing of openly racist Police Chief Doc Vaughn, in part over his brutal attacks on African Americans; and the 1946 circuit court ruling that forced the city to end its practice “Whites only” primary elections, which they’d conducted in defiance of two U.S. Supreme Court rulings in 1941 and 1944.

City leaders had made several attempts to reassert the boundaries of Blackness in St. Petersburg, e.g., in 1946, City Council banned African Americans from downtown except when working by making it unlawful to sell to or serve “any colored person in a place of business maintained for the white race.”

But by 1948, it was clear that the tide was beginning to turn. City Council was at a loss for how to contain the City’s roughly 13,000 Black residents in the four small neighborhoods set apart for their use.

Tensions reached a boiling point in February of that year after city leaders (in a last-ditch effort to find a solution to the “Negro area problem”) tentatively proposed to expand the territory where African Americans were permitted to buy or build homes.

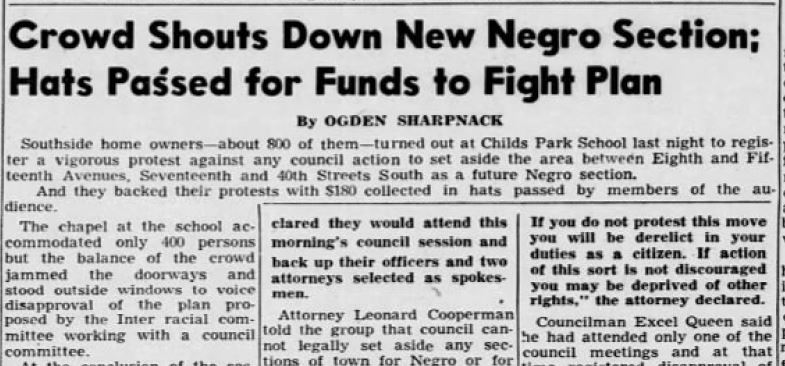

A crowd of 800 white residents gathered on February 16th to mount a protest against the plan, raising money on the spot for a campaign to fight the proposal and staging a march on city hall the next day.

The following week, Vice Mayor Johnson attempted to quell the outcry by prostrating the city’s legislative branch before the white public.

At a February 22nd City Council meeting, he outlined some of the not “purely legal” actions the city had taken to inhibit Black residents’ mobility, and made it clear that City Council would heed the wishes of their overwhelmingly white electorate going forward.

Here is what Johnson said.

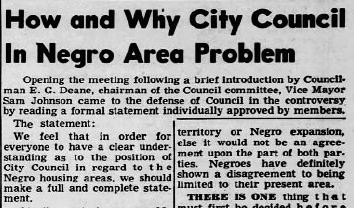

City Council Statement re Efforts to “Protect White Areas” [Feb 22, 1948]

Samuel Johnson, Photo featured in St. Petersburg Times, October 16, 1945

We feel that in order for everyone to have a clear understanding as to the position of City Council in regard to the Negro housing areas, we should make a full and complete statement.

At the outset we would like to say that the City Council had no desire to become involved in Negro segregation whatsoever, nor do we now wish to be involved. The present City Council is fully aware, as were other Councils before us, that we have absolutely no legal right to establish any segregated areas for Negro housing, nor have we any right as a matter of law to establish any restrictions or zones for either white or colored people.

City Council never wished to be involved in this question and is involved in it now simply because in the past numerous white property owners in the vicinity of the Negro area have repeatedly called upon Council to prevent an encroachment of Negroes into the area in which they live.

At first they insisted Council pass a Negro segregation ordinance, but such an ordinance would be utterly unenforceable at law. We have had some difficulty in attempting to explain that the city did not have this right to enact a valid segregation ordinance, that the Supreme Court of the United States and the Supreme Court of practically every state in the Union has declared ordinances of this type unconstitutional.

After explaining our inability to take legal steps we were beseeched by numerous people to take other than purely legal steps in an attempt to eliminate or restrict uncontrolled Negro expansion into white areas.

In our endeavor to protect white areas from uncontrolled Negro expansion we have may gone beyond what was technically our concern.

The building department of the city discouraged Negroes when they made applications for permits within the white areas, realizing, of course, that it had no legal right to refuse these permits, if they were definitely insisted upon. This action was taken only to protect white areas and was taken at the earnest insistence of many white property owners.

On some occasions when it became obvious that Negro applicants for building permits could not be persuaded to withdraw their applications, the city actually purchased the property upon which the permit was sought, with the understanding that Negroes would purchase other property located clearly within the Negro section.

Perhaps we have no legal right to do this and we were in error. Perhaps it would have been better, and it would certainly have been easier, to have taken no action whatever and simply stated that by reason of our inability to control legally Negro expansion our hands were tired. If we accept the proposition that City Council has no business to interfere in any way with either Negro or white expansion, it is clear that we were wrong.

When our attempt seemed futile, because we could not continue indefinitely to persuade Negroes who had purchased property in the white areas not to build on their property – and we certainly could not continue a policy of purchasing property from Negro applicants for building permits – we in desperation referred the matter to the Inter-Racial Committee in the hope it could work out a solution agreeable to both white and colored.

It was naturally considered by the committee that any sort of agreement would have to provide at least some additional territory or Negro expansion, else it would not be an agreement upon the part of both parties. Negroes have definitely shown a disagreement to being limited in their present area.

There is one thing that must first be decided before there is any necessity for our discussion to proceed further. This Council must know whether or not the residents in the vicinity affected want us to attempt not by law, but by arbitration, to establish an agreed area for Negro housing or whether they feel that this matter is of no concern of Council and wish us to withdraw from any attempt to establish such an agreement.

At the last Council meeting one spokesman severely censored Council for attempting to interfere with either white or Negro expansion. If we correctly construe his remarks, they were to the effect that this Council has nor right, and should not attempt, to establish any area to be devoted to Negro housing and neither should it attempt in any manner to interfere with or prevent Negro expansion into white areas.

If that is the desire of the people in this neighborhood, if they do not wish the City Council to attempt by arbitration to establish agreed upon areas for white and colored, it is much better that we, as City Council, withdraw completely and, as your spokesman suggested, leave this matter to its natural adjustment.

On the other hand, if it is the desire of the people in this community that some agreement be attempted and they want this Council to try to promulgate this agreement, we may be willing to attempt it, as difficult as it may be. We definitely, however, will not attempt to arbitrate any agreement or proceed further in this matter confronted with an atmosphere of hostility, suspicion and mistrust.

We wish to call your attention to the fact that the area proposed by the Inter-Racial Committee was simply a starting point. In other words, the committee had to start somewhere. Those of you who have familiarized yourselves with the committee’s report must be fully aware that this area was proposed for primary discussion only and did not purport and was not intended to be a definite expression of the committee, much less of City Council, as to the ultimate areas that would be set aside for Negro areas.

If this Council should continue with this matter, it might be that a solution to the problem could be had through increased Negro facilities in the areas now occupied by them. Multiple housing units and improvement of the physical facilities in this area might be a solution to the problem upon which the Negroes would agree. All of this, however, is a matter for thought and discussion and a final decision should be made after mature and intelligent consideration of all factors involved.

Neither you nor the Council can solve this problem through emotion. It must be brought out and decided to the best interest of the city as a whole and to you more particularly who are directly affected. As you have so ably demonstrated, any attempt upon the part of the City Council to even attempt to consider this matter has led to misunderstandings, unjust criticism and unwarranted suspension.

You may be assured that this Council does not wish to become involved in any issue that would lead to strife or bitterness. We would much rather completely withdraw from this matter and leave it entirely in your hands, and if this is your desire, we will gladly do so; it is up to you.

What Happened Next

In the years following Johnson’s remarkable admission, City Council continued efforts to block and slow the pace of Black housing development. Johnson went on to serve three two-year terms as mayor, during which St. Petersburg experienced its biggest ever white residential housing construction boom.

All the while, city officials and staff openly colluded and sided with white property owners, developers, and activists to prevent the territorial expansion of housing development for and by African Americans. They also impeded the establishment of minimum housing standards in Black neighborhoods that would have elevated property values and quality of life for the thousands who lived there.

In September of 1948 (seven months after the brouhaha chronicled above) City Council did approve an expansion of the “Negro area” but by less than one-fifth the landmass proposed earlier in the year.

Researchers at the University of South Florida St. Petersburg will soon unveil a study on structural racism in St. Petersburg that documents some of this history.