News

Timeline: 40 Years of Broken Promises to the Black Community Over the Trop; What We Lost, and What to Watch for as Developers Present Their Equity Concepts This Week

– Gypsy C. Gallardo for One Community, Power Broker magazine & TheBurgVotes.com

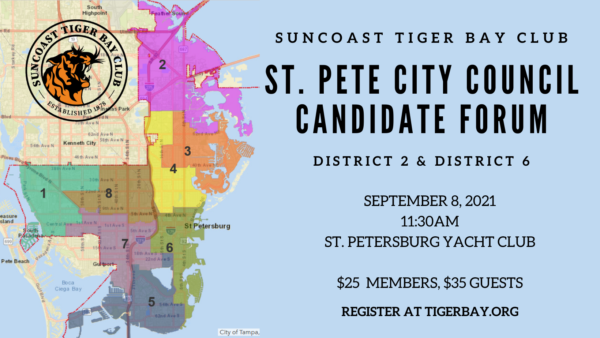

This evening at 6 pm, the City of St. Petersburg will host the first in a series of three public forums for citizens to learn more about the four shortlisted proposals for redevelopment of Tropicana Field (also known as “the Trop”).

African Americans and other equity advocates will be watching closely. Not only because the Trop is the largest redevelopment project ever undertaken in South St. Pete, where 75% of the city’s black residents live. The Trop is also the site of one of the largest mass displacement of African Americans in City history, and at long last, St. Pete is committed to redressing that fact.

Eight mayors have presided over developments there, but Rick Kriseman is the first to make race equity a guiding standard for the project’s future. And unlike shallow efforts of the past, Kriseman is asking for an equity focus in every facet of the project, from development and investor teams, to construction contracting and hiring, to affordable housing and commercial spaces, and public art that captures the history of the site and its vision of authentic inclusion.

Advocates are on alert to ensure those promises are enshrined in the development agreement the Mayor hopes to cement by October.

This article was written to remind us of what we lost when the City decided to build a stadium, and the lessons learned from repeated failures to meet equity goals for past developments there.

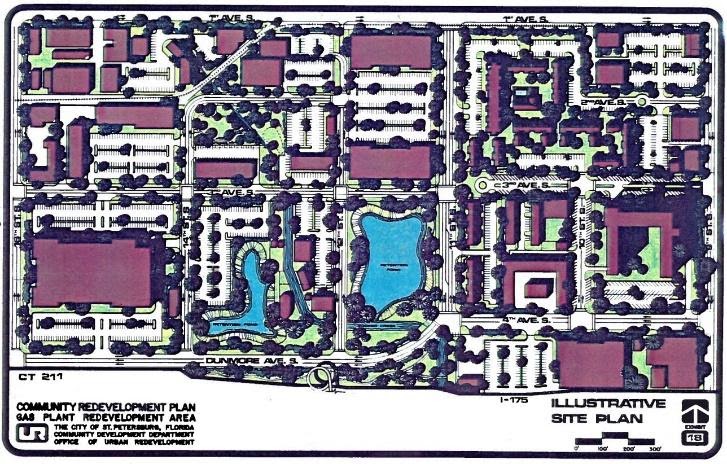

Part 1 – The Abandoned Plan for Gas Plant Redevelopment

Many city residents have heard the tale, but few realize the scale of displacement that happened at the site, or the consequences in its wake.

The part of the story often told is that in 1979, the City approved a plan to redevelop the all-black Gas Plant area with commercial spaces that would create 680 jobs paying $20 million in wages (today’s dollars) plus construction jobs over seven years to rehab and build new homes.

But the plan was shelved by 1986, when City Council voted to build a baseball stadium instead, which would bulldoze 285 buildings, relocate 9 churches and 500 households, cause 40 businesses to move or close, uproot organizations such as the Masons, and demolish 80+ investment properties, many black-owned.

What isn’t widely known is that Gas Plant was the seventh mass displacement over a dozen years that relocated 2,100 black families, businesses, and institutions from their homes in St. Pete’s segregation-era black neighborhoods.

Methodist Town was the first casualty. In 1974, City leaders introduced a plan to rehab and build 165 homes and a community center there. But black leaders of the day say they were betrayed. “When the City finished its work, the area’s past was preserved only by Bethel AMEand three other churches…this once thriving community did not have a grocery store within 10-miles by 1985”and 377 families had been displaced.

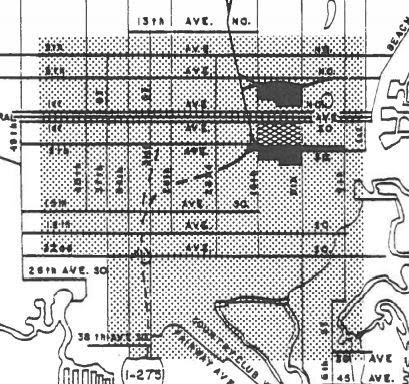

That was followed by phased construction of Hwy I-275 which sliced through the heartof the black community, razing 1,200 homes, businesses, non-profits, and churches; while severing the beloved Gibbs Highfrom areas housing hundreds of its alumni; dead-ending the high-traffic 15thAvenue; and destroying historic properties.

Nearby, completion of I-175 in 1980 began the demise of the affluent black area called Sugar Hill, on Gas Plant’s southern border.

Officials tried to quell black leaders’ complaints by pointing out that I-275 dislocated 900 white households too. But there was no comparison. Despite being only 16% of the population, twice as many African Americans were displaced.

These are only a few of the dozens of acts of economic oppression and disruption in the years leading up to the Gas Plant displacement.

The City had said that it would “encourage the deconcentration of minorities” by relocating them “to non-traditional neighborhoods, where housing was affordable to “the displacee.”

That was seen as positive by many, black and white, after decades of willful neglect of dangerous and dilapidated housing in black areas. Indeed, records show some relocations resulting in higher-value homes for displaced families.

Whatever the net change in housing costs and con-ditions for the 4,000 blacks relocated during the era, Gas Plant’s destruction was a final death knellfor the business and institutional strength of Black St. Pete at its segregated peak.

By the time dome construction started in 1987, two decades of urban renewal and integration had evisceratedthe once bustling core of black life and commerce in St. Pete, and dissipatedthe once captive black consumer who increasingly spent her dollars with white-owned firms.

As one indicator of the damage done, the Census showed a rapid drop in the number of black-owned employer firms in St. Pete, from 174 in 1987 to 86 by 1992. The city still hasn’t reclaimed that peak. The latest data show 144 black employer firms.

In 1960, 90% of Black St. Pete lived, socialized, shopped and went to church within 2.5 square miles that hummed with the vitality of 100+ civil rights, service and business organizations.

By 1990, that mass was scattered over 25 miles, and a once socioeconomically diverse community was well into the process captured in the 2010 book Disintegration: The Splintering of Black America. Black St. Pete was quickly shifting into distinct and ever more disconnected groups.

The community would never return to its heyday when most every black family was part of the communal life of church, school, and service. As one Pastor said in 2008, we are two generations removed from when most of our children were churched. We lost much more than 285 buildings when the Gas Plant neighborhood was destroyed.

Part 2 – Minority Goals for Dome Construction 1987

From day one, the prime contractor selected to build the Florida Suncoast Dome (later renamed Tropicana Field) struggled to meet the City’s MBE subcontractor goal for the project. So much so that the firm – Huber, Hunt & Nichols (HHN) of Indianapolis – appears to have lied about or at least significantly fudged its numbers to the City.

Construction of the dome lasted three years (1987 to 1990) and was originally expected to cost $85 million. Of that, less than half or $39 million was subject to the City’s 10% goal for Minority Business Enterprise (MBE) participation, which would equal $3.9 million in contracts for black, Hispanic, and women-owned firms combined.

Even that modest target proved too much for HHN. In November 1997, the City’s MBE Coordinator Theresa Jonesreported that less than 1% of contract dollars had been awarded to certified minority-owned firms, contradicting HHN’s claim to have met half its MBE goal by then, with $2 million already awarded to MBEs.

Jones committed to verify whether the contractors were “legitimately minority-owned.” Her count showed that by January 1988, only 2.6% of the project had gone to certified MBEs ($1 million in all). She issued a scathing letter that February, urging HHN to step it up. “We are extremely concerned,” she wrote. “In light of the fact that one year of construction is complete, it is imperative that additional measures be taken.”

It appears HHN heeded the warning and by April 1988 had awarded 4.5% of the project to MBEs. By the end in 1990, the City reported 7.6% MBE participation, which though short of the 10% goal, was vast progress from the City’s 1% MBE spend in 1985 and HHN’s poor showing in 1987.

From there the story gets fuzzy. We don’t know what sum to apply that 7.6% to, because by 1990, the cost of the dome had ballooned to $130 million (and by 2008, the Tampa Bay Times was reporting $233 million), and it’s unclear what portion of that total had MBE goals tied to it.

We also don’t know how much went to black-owned firms. If they were half of all MBEs, and if MBE goals applied to 30% to 40% of the project ($39 to $52 million), the dome resulted in about $1 to $2 million in contracts for black MBEs. That equates to around 1.1 to 1.5 % of the total $130 million project, or a penny or so on the dollar. The net result echoed a May 1990 report on a City-funded study into whether routine discrimination still existed in City contracting. The study found that “A history of discriminatory city laws and exclusion from a tight group of private business leaders have helped create a situation in which minorities do not get their fair share of business” and that while the City had made progress, it still had not risen above the “good old boy network” that still won a lion’s share of City contracts.

Part 3 – Minority Goals for Trop Renovation in 1997-98

A decade later, the City had its third shot at the equity apple during the $62 million renovation of the dome, completed in 1998, to serve as the new home of the Tampa Bay Devil Rays.

Once again, the project unperformed against MBE goals set by the City. Though I’m still working to secure a final tally, we have a partial picture from a Times report in April 1997 by Adam Smith.

By then, two-thirds of project contracting was already decided ($39.9 million), and against the City’s 13% goal for MBE contracts ($5.2 million), only 8% had so far gone to MBEs ($3.2 million).

Worse, only $1.1 million had gone to black firms. Worse still, in January 1998, one of the largest MBE contracts ($750,000) was cancelled by the City, with a public rebuke to two black firms – Barrow Construction and Curtoom Group whose owner wrote on January 9th“Curtoom is outraged that the city has had the colossal arrogance to appoint itself as judge, jury and executioner in the matter of Curtoom vs. Barrow.”

As I await documents to confirm the final MBE target reached on the project, we can at least estimate. If MBE contracts continued at the same rate for the life of the 15-month renovation, MBEs may have won $4.96 million in contracts, and black-owned firms may have won about $1.8 million, equal to 8% and 2.8% of the project.

I can also say that nowhere in the City’s 123-page Agreement with the Rays do I find MBE goals or any other type of community benefits. In fairness, I may have missed them.

The Rays appear to have had no role in reaching the MBE goal, based on the 1997 Times article. Smith wrote “Rays officials were quick to distance themselves from the MBE effort. You’ll have to talk to the city about that,” snapped Managing General Partner Vince Naimoli.”

Lessons learned though. This time, equity advocates are calling for a Community Benefits Agreement as part of the City’s deal with the chosen developer. And if the Rays choose to remain on the site, we’re asking that they use their leverage to help ensure it comes to pass.

This way, “The Community Wins, No Matter Who Wins” (the motto now circulating among advocates closely tracking the process). n

This post is the first in a series of articles the Power Broker magazine will publish about the quest for equity in the redevelopment of Tropicana Field. Its author Gypsy Gallardo is a member of the Bloomberg-Harvard City Initiative Team for Equity at Tropicana Field. She is also CEO of the One Community Plan, a 10-year initiative to “grow the paychecks, bank accounts and balance sheets of African Americans in St. Petersburg,” as well as 2021 Chair of the Grow Smarter at the St. Petersburg Chamber, a citywide collective impact initiative for equity.